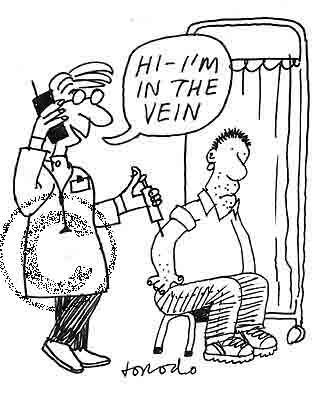

"Ay, sori po. Nag-bulge po kasi manipis ang ugat nyo." (Sorry Ma'am. It bulged because your veins are thin and collapsible.)

These things do happen. And it happened to me more than once. And I dread it.

The reasons why the staff at the nurses' station page us interns at unholy hours of the night are because of the following:

1. Skin test (determining if the test antibiotic is allergic to the patient prior to starting the dose)

2. IV push (pushing several cc's of medications via IV lasting as long as 30 minutes)

3. NGT insertion (inserting a plastic or silicone tube through the nose to the stomach)

4. Indwelling Foley Catheterization (placing a rubber catheter into the urethra of female/male patients to monitor urine output)

5. Straight Catheterization (inserting temporarily a rubber catheter into the urethra for urinalysis or bladder relief)

6. Medical Abstract (writing time-consuming clinical summaries for patients)

7. IV insertion (inserting a needle into the hands or arms so as to have an IV access)

8. Change of Dressing (cleaning and debriding wounds and changing the gauze for new ones)

These procedures have varied levels of grossness and nausea, with routine exposure to them made most of us jaded and callous with nary a tinge of malice to them. Most are easily and quickly done with a step-by-step operation.

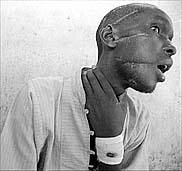

Only the IV insertion proves to be the most challenging of the tasks. Ask any doctor. So, if the nurses can't do it, they'll call the interns. If the interns cannot do it, they'll call in the residents. And with such a totempole set-up, it is inevitable that the patient's hands have now turned into a dartboard of blotched IV insertions or an exploded minefield full of dark red and purple bruises. But most of the time, it's a one shot deal- so no complaints there.

Sometimes, the nurses coerce the interns to take the first plunge- especially if the veins at hand are hidden and difficult to ascertain, or if the patients have a terribly low threshold for pain, or if the relatives are a pain in the ass. The most dreaded patient to be inserted are the elderly (due to thin collapsible veins), fat people (because their veins are hidden inside those pads of fat), and children (because they and their mothers are so irritable that you want to suture their lips.) And if the patient's relatives would ask, "Magaling ka ba? Sharpshooter ka ba? Kailangan isang turok lang!," I'd tell them silently, "Ikaw na lang kaya mag-swero, you stupid ass!" Of course, I can't tell them that, so I would smile at them and would tell them that I'll try my best.

And so, sometimes you shoot, sometimes you don't. If you do shoot, it feels like as if a fishbone has been extracted from your throat. If not and it did bulge, I would always tell them that it's their veins' faults. It's their vein's fault that it's collapsible, that the vessels are deeply set, or that they do not stay in place. This is coupled with a distraught face, knotted eyebrows, a frustrated sigh and profusion of sorry's to ebb the tide of patient's anger for not shooting in one go. Doctors are human too.

The good thing is, most patients are very patient and understanding that they do not make a fuss or create a scandalous scene when they are entreated to another insertion. This should never be construed that we in the medical field are happy-go-lucky in inserting needles into patient's hands. We try our best to minimize it, but if it happens, we can only learn from it so that in the future, we can avoid it.

It's still a relief that here in the Philippines, there is no culture of lawsuits unlike the United States where a mere blotched IV insertion can be grounds of getting sued. But if the medical malpractice bills (3 already) will be passed, then doctors can be sued over this. If that's the case, then every nurse and doctor will pass this noble job of IV insertion to the Phlebotomist.

Dr. Rolour Garcia, a '92 graduate of West Visayas has this to say about traumatic IV insertion:

IV insertion is a skill that you don't acquire by practicing on a dummy, it's by doing it frequently over a span of time on real patients. You become good at it not because you graduated at the top of your class, it's simply because you have done a lot of it on a regular basis. The same is true for other procedures, whether minor or major as in surgical or obstretric cases (in procedures where a simple rookie mistake can mean life or death, newbies are always accompanied by seasoned veterans). Hitting a muscle instead of a vein is always possible if you are just starting and new to it. I would not even call it "practicing" because you have to start somewhere and beginners usually mess it up more than the veterans. Of course, there are other factors to why interns or doctors may not do it right the first time - like obese patients, collapsed veins (severe dehydration, Rolling Stones' Keith Richards) or simply, human error (sleep-deprived, too much caffeine). Having worked in a government hospital, I can say that most, if not all, patients understand that accidents or complications could occur, and without sounding impartial, doctors usually do a good job in explaining it to them. The problem here is when lawyers, legislators and insurance companies start "educating" the patients themselves that these are not just "accidents" but "negligence" that doctors should pay for with money and prison time. The government as well as the medical community may have failed in adequately educating the patient but that doesn't mean other sectors of society should take advantage of it.

As they say, practice makes perfect! So, during my current stay in IM, my IV insertion skill is being honed and polished thanks to the multitude of practice hands my patients have given me. My confidence (and thankfully, my success rate) have been progressively growing during these past weeks. At first, I dread when the nurses call for an insertion, but now, I treat it as a routine procedure. A little patient pep talk, lots of concentration, and presto! Shoot kaagad. Hopefully, it will stay way.